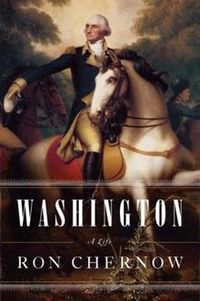

From Ron Chernow's Washington: A Life:

From Ron Chernow's Washington: A Life:

The idea that abolition could be deferred to some future date when it would be carried out by cleanly incremental legislative steps was a common fantasy among the founders, since it shifted the burden onto later generations. It was especially attractive to Washington, the country’s foremost apostle of unity, who knew that slavery was potentially the country’s most divisive issue. (p 490)

Regarding the Constitutional Convention:

The delegates agreed that slavery wouldn’t be mentioned by name in the Constitution, giving way to transparent euphemisms, such as “persons held to service or labor.” (p 536)

For the purposes of representation in the House of Representatives and the Electoral College, (slaveholders) would be able to count three-fifths of their slave population. This was no mean feat: slaves made up 40 percent of the population of Virginia, for instance, and 60 percent in South Carolina … masters would be able to reclaim runaway slaves in free states – a provision George Washington would liberally employ in future years. (p 536)

… the abolitionist William Loyd Garrision would later castigate the Constituiton as “a covenant with death and an agreement with hell." (p 537)

After Washington left office:

THE MOST FLAGRANT OMISSION in Washington’s farewell statement was the subject most likely to subvert its unifying spirit: slavery. Whatever his private reservations about slavery, President Washington had acted in accordance with the wishes of southern slaveholders. In February 1793 he signed the Fugitive Slave Act, enabling masters to cross state lines to recapture runaway slaves. He remained zealous in tracking down his own fugitive slaves ... (p 758)

His most flagrant failings remained those of the country as a whole—the inability to deal forthrightly with the injustice of slavery or to figure out an equitable solution in the ongoing clashes with Native Americans. (p 771)

He saw, with some clairvoyance, that slavery threatened the American union to which he had so nobly consecrated his life. “I can clearly foresee,” he predicted to an English visitor, “that nothing but the rooting out of slavery can perpetuate the existence of our union, by consolidating it in a common bond of principle.” Beyond moral objections to slavery, he had wearied of its immense practical difficulties. (p 800)

Regarding freeing his slaves when he and his wife died:

By freeing his slaves, Washington accomplished something more glorious than any battlefield victory as a general or legislative act as a president. He did what no other founding father dared to do, although all proclaimed a theoretical revulsion at slavery. (p 802)

If he had hoped that other slave masters would emulate his example in liberating his slaves, he was cruelly mistaken. (p 811)

Richard ...

I did not know until I began reading these presidential biographies how much slavery was an issue in the United States from it's founding.